Selected projects & publications

Multitask representation in the prefrontal cortex

The topographic maps reveal how neurons carrying out similar computations are organized in the brain. For instance, in the primary visual cortex, neurons preferring similar polar angles and eccentricities are organized in pin-wheel patterns, mapping the external world onto the visual cortex.

How about the prefrontal cortex (PFC)? PFC supports multiple higher-order cognitive functions, such as working memory, decision making, and motor planning. PFC neurons flexibly adapt their activity according to rules, contextual associations and feedback. Do topographic maps exist in PFC as in visual regions? If so, how do they look like? How are different tasks inter-related in the brain? Addressing these questions will allow us to understand how our brain supports so many higher-order cognitive tasks flexibly.

Xiang et al. (2025). Toward task mapping of primate prefrontal cortex. Neuropsychologia. paper

Xiang et al. (2025). Task-specific topographic maps of neural activity in the primate lateral prefrontal cortex. Nature Communications. (under review) paper

Compositional representation of tasks in human brain

The execution of complex cognitive tasks repeatedly activates an extensive networks of frontal and parietal regions, known as the multiple-demand (MD) system, whose distributed activity patterns carry information about the task. However, the functional organization of task representation remains unclear. Do certain tasks elicit more similar activity patterns than others? If so, what drives the functional organization?

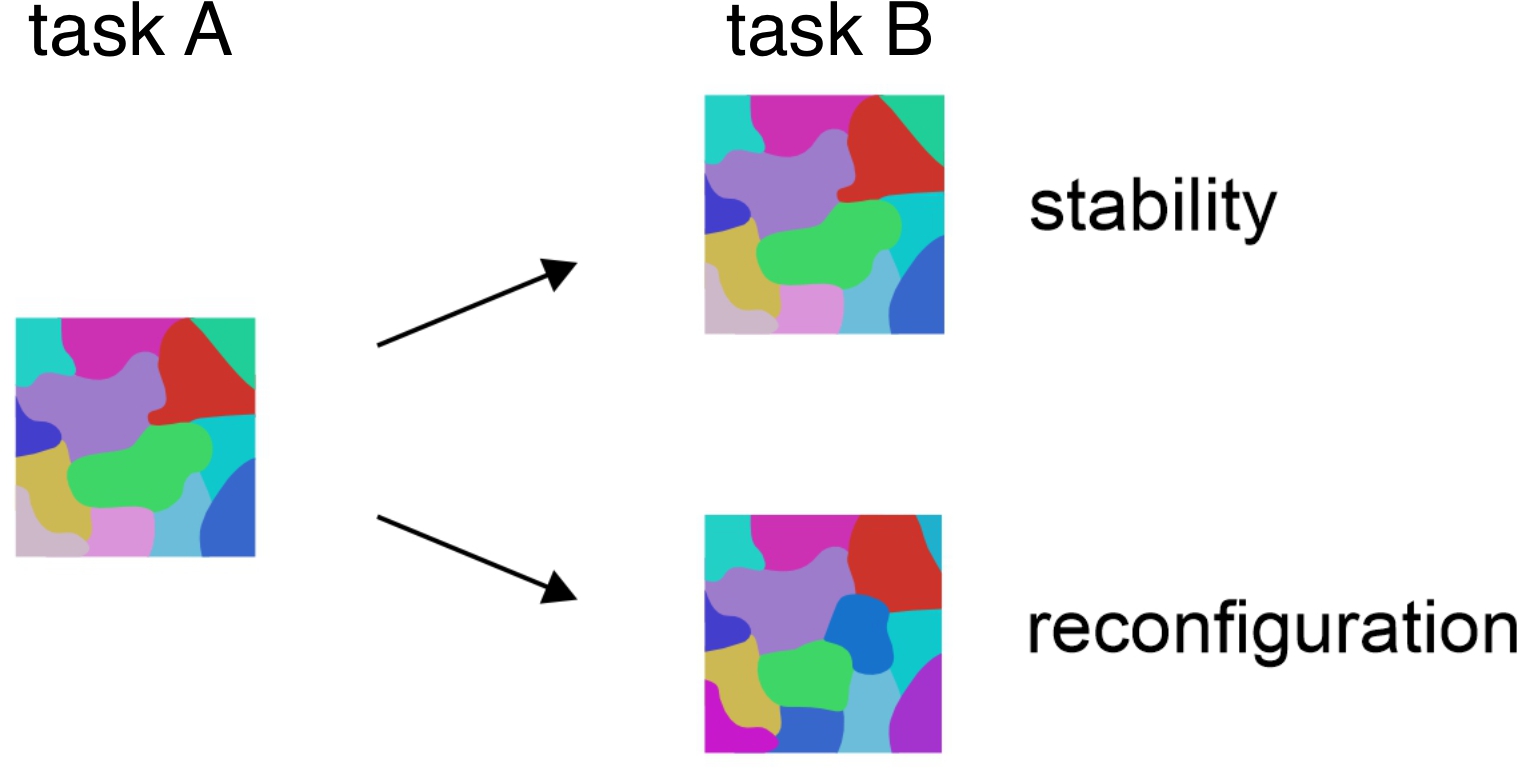

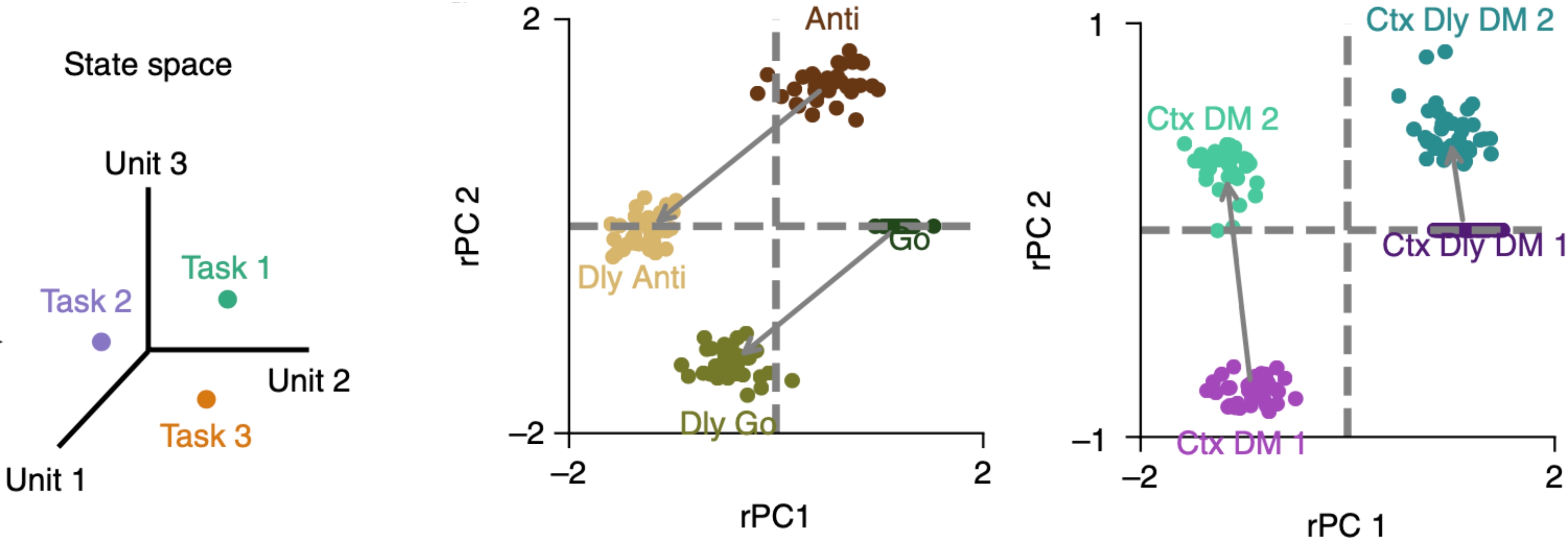

Computational work suggests that asks may be represented in a compositional fashion in PFC, where the representation of a task can be expressed as the algebraic sum of vectors representing the underlying sensory, cognitive and motor processes. Empirical evidence for compositional coding is limited. It remains to be tested if this principle generalizes to tasks that require context-dependent decisions. In this work, we provide empirical support for composition coding.

Figure adapted from Yang et al. (2019). Nature Neuroscience

Xiang et al. (2024). Compositional representation of tasks in human multiple-demand cortex. Organization for Human Brain Mapping. abstract, poster

Model selection and inference

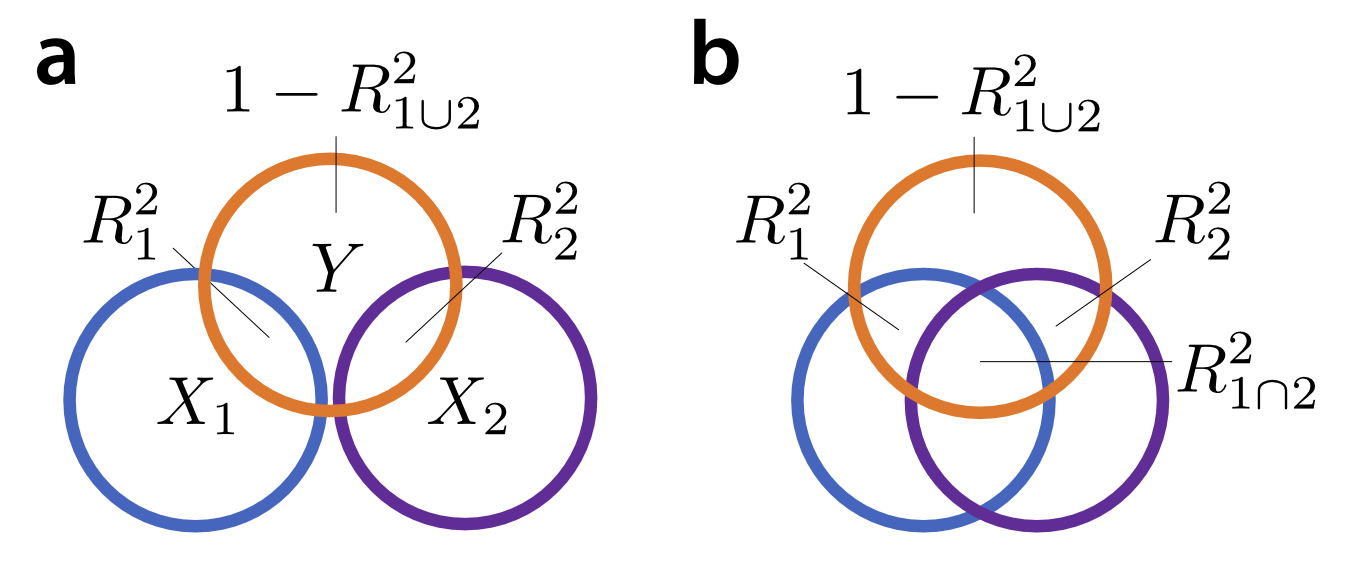

In the context of statistical modelling, one often comes across the idea of variance partitioning, which quantifies how variance of a variable can be explained by an experimental feature. The idea of variance partitioning in linear models goes back to Fisher’s ANOVA (Fisher, 1925). The proportion of variance explained by a certain set of predictors is the value for that model. In the case of a balanced ANOVA, where $X_1$ and $X_2$ are orthogonal, the variance explained by the joint model that combines the two regressors ($R^2{1\cup2}$) is the sum of the variance explained by each one alone ($R^2{1}+R^2_{2}$) (panel a).

The trouble starts when we try to generalize this intuition to the more general case in which $X_1$ and $X_2$ are correlated (panel b). One of the problems is that the shared variance $R^2_{1\cap2}$ could go negative, due to suppression effect, which could render results uninterpretable or mislead conclusions. The explained variances for simple models and their combinations do not behave like a Venn-diagram. We propose a quantitative framework for model selection and inference.

Xiang et al. (2025). Variance explained by different model components does not behave like a Venn diagram. Cognitive Computational Neuroscience. abstract, poster, blog

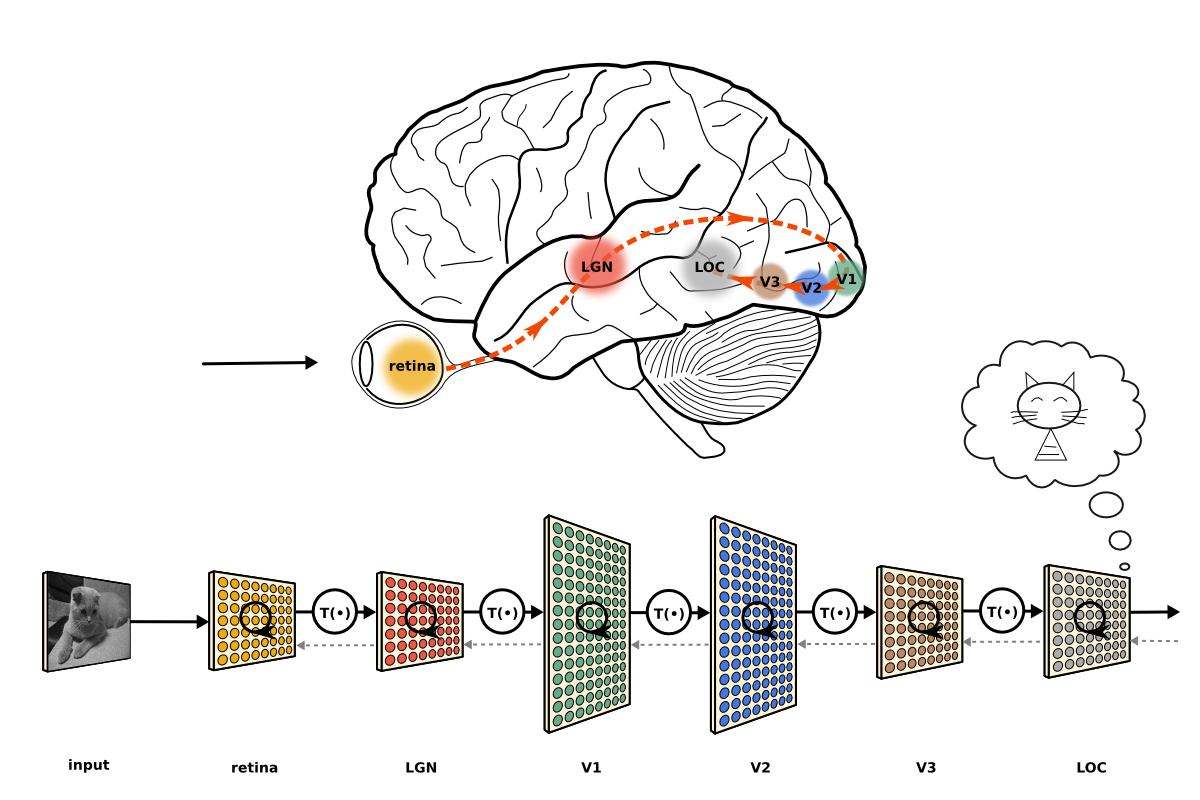

Comparing computer vision models vs. human visual perception

Computer vision models, such as deep neural networks, can achieve human-level performance in many tasks, e.g. visual classification. Do neural networks and human visual brain regions carry out similar computations? If two objects are represented similarly by a neural network, are they also represented similarly in human brain? We address these questions empirically by comparing the object representations in AI models and human visual brain regions.

Behavioral inflexibility in addictions

Behavioral flexibility, the ability to adapt behaviors in response to changes in the environment, is of great importance for everyday functioning. Behavioral flexibility is typically assessed using reversal learning tasks, in which subjects learn to perform a specific action to receive a reward, then must alter their behavior when a different action is rewarded instead. Impairments in such flexibility are observed in substance use disorder, characterized by persistent drug use despite negative outcomes. Individuals with substance use disorders may choose to use drugs even when more rewarding alternatives are available especially in contexts that were previously associated with drug use. Similar features of behavioral inflexibility appear in animal models exposed to cocaine and may manifest through subjects selecting a previously rewarded object when more highly rewarded objects are subsequently presented. We ask how behavioral inflexibility could be explained from a neural population coding perspective in animal models.

Figure adapted from Mueller et al. (2021). Journal of Neuroscience

Xiang et al. (2021). Behavioral inflexibility from a neuronal population perspective. Journal of Neuroscience paper